http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3174T-3-59Q&feature=player_embedded

-------------------------

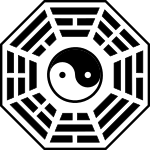

Tao

| Taoism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fundamentals | |

| Dao (Tao) ·De (Te) ·Wuji ·Taiji ·Yin-Yang ·Wu Xing ·Qi ·Neidan ·Wu wei | |

| Texts | |

| Laozi (Tao Te Ching) ·Zhuangzi ·Liezi ·Daozang | |

| Deities | |

| Three Pure Ones ·Yu Huang ·Guan Shengdi ·Eight Immortals ·Yellow Emperor ·Xiwangmu ·Jade Emperor ·Chang'e ·Other deities | |

| People | |

| Laozi ·Zhuangzi ·Zhang Daoling ·Zhang Jue ·Ge Hong ·Chen Tuan | |

| Schools | |

| Tianshi Dao ·Shangqing ·Lingbao ·Quanzhen Dao ·Zhengyi Dao ·Wuliupai | |

| Sacred sites | |

| Grotto-heavens ·Mount Penglai | |

In Taoism, Chinese Buddhism and Confucianism, the object of spiritual practice is to 'become one with the tao' (Tao Te Ching) or to harmonise one's will with Nature (cf. Stoicism). This involves meditative and moral practices. Important in this respect is the Taoist concept of De (virtue).

In all its uses, Dao is considered to have ineffable qualities that prevent it from being defined or expressed in words. It can, however, be known or experienced, and its principles (which can be discerned by observing Nature) can be followed or practiced. Much of East Asian philosophical writing focuses on the value of adhering to the principles of Tao and the various consequences of failing to do so. In Confucianism and religious forms of Daoism these are often explicitly moral/ethical arguments about proper behavior, while Buddhism and more philosophical forms of Daoism usually refer to the natural and mercurial outcomes of action (comparable to karma). Dao is intrinsically related to the concepts yin and yang (Pinyin: yīnyáng), where every action creates counter-actions as unavoidable movements within manifestations of the Dao, and proper practice variously involves accepting, conforming to, or working with these natural developments.

The concept of Tao differs from conventional (western) ontology, however; it is an active and holistic conception of Nature, rather than a static, atomistic one.

Description and uses of the concept

The word "Dao" (道) has a variety of meanings in both ancient and modern Chinese language. Aside from its purely prosaic use to mean road, channel, path, doctrine, or similar,[1] the word has acquired a variety of differing and often confusing metaphorical, philosophical and religious uses. In most belief systems, Dao is used symbolically in its sense of 'way' as the 'right' or 'proper' way of existence, or in the context of ongoing practices of attainment or of the full coming into being, or the state of enlightenment or spiritual perfection that is the outcome of such practices.[2] Some scholars make sharp distinctions between moral or ethical usage of the word Dao that is prominent in Confucianism and religious Daoism and the more metaphysical usage of the term used in philosophical Daoism and most forms of Mahayana Buddhism;[3] others maintain that these are not separate usages or meanings, seeing them as mutually inclusive and compatible approaches to defining the concept.[4] The original use of the term was as a form of praxis rather than theory - a term used as a convention to refer to something that otherwise cannot be discussed in words - and early writings such as the Dao De Jing and the I Ching make pains to distinguish between conceptions of Dao (sometimes referred to as "named Dao") and the Dao itself (the "unnamed Dao"), which cannot be expressed or understood in language.[notes 1][notes 2][5] Liu Da asserts that Dao is properly understood as an experiential and evolving concept, and that there are not only cultural and religious differences in the interpretation of Dao, but personal differences that reflect the character of individual practitioners.[6]

Dao can be roughly thought of as the flow of the universe, or as some essence or pattern behind the natural world that keeps the universe balanced and ordered.[7] It is related to the idea of qi, the essential energy of action and existence. Dao is a non-dual concept - it is the greater whole from which all the individual elements of the universe derive. Keller considers it similar to the negative theology of Western scholars,[8] but Dao is rarely an object of direct worship, being treated more like the Hindu concepts of karma or dharma than as a divine object.[9] Dao is more commonly expressed in the relationship between wu (void or emptiness, in the sense of wuji) and yinyang (the natural dynamic balance between opposites), leading to its central principle of wu wei (non-action, or action without force).

Dao is usually described in terms of elements of nature, and in particular as similar to water. Like water it is undifferentiated, endlessly self-replenishing, soft and quiet but immensely powerful, and impassively generous.[10] Much of Daoist philosophy centers on the cyclical continuity of the natural world, and its contrast to the linear, goal-oriented actions of human beings.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tao